What Else Can Physiotherapy Do?

Becoming Nomads

No problem can be solved from the same level of consciousness that created it — Albert Einstein

The body is a Russian doll. A thing to be unravelled and known. Any one part can be better understood by analysing its smaller parts.

Or so the popular fable goes. This particular approach provides us with particular solutions. But one perspective, one vantage point, is hardly exhaustive or sufficient enough to reflect or account for the diversity of life.

The painter does not paint on an empty canvas, and neither does the writer write on a blank page; but the page or canvas is already so covered with preexisting, preestablished cliches that it is first necessary to erase, to clean, to flatten, even to shred, so as to let in a breath of air from the chaos that brings us the vision. — Deleuze and Guatarri1

What if we allowed ourselves the luxury of viewing the body from a different perspective than the one which we were handed, one different to that which proliferates much of our professions today? We have been steeped in the implicit assumptions that biology and biomedicine can fully account for the body, without being taught that these were merely the foundations on which physiotherapy and medicine were built. What if we entertained a perspective of relations between or among bodies?

It has been customary to divide health up into the biological, psychological and social in an attempt to provide a more “holistic” flavour of care. However, we don’t seem to have the ability to escape the gargantuas gravity of biomedicine2. Any attempt to adsorb the social and psychological in the clinic has not resulted in a more even substrate, but rather has led the psychosocial to be held hostage by biomedicine. After years of good behaviour, it has been allowed the privilege of being described in terms of biology but never to be seen as equals.

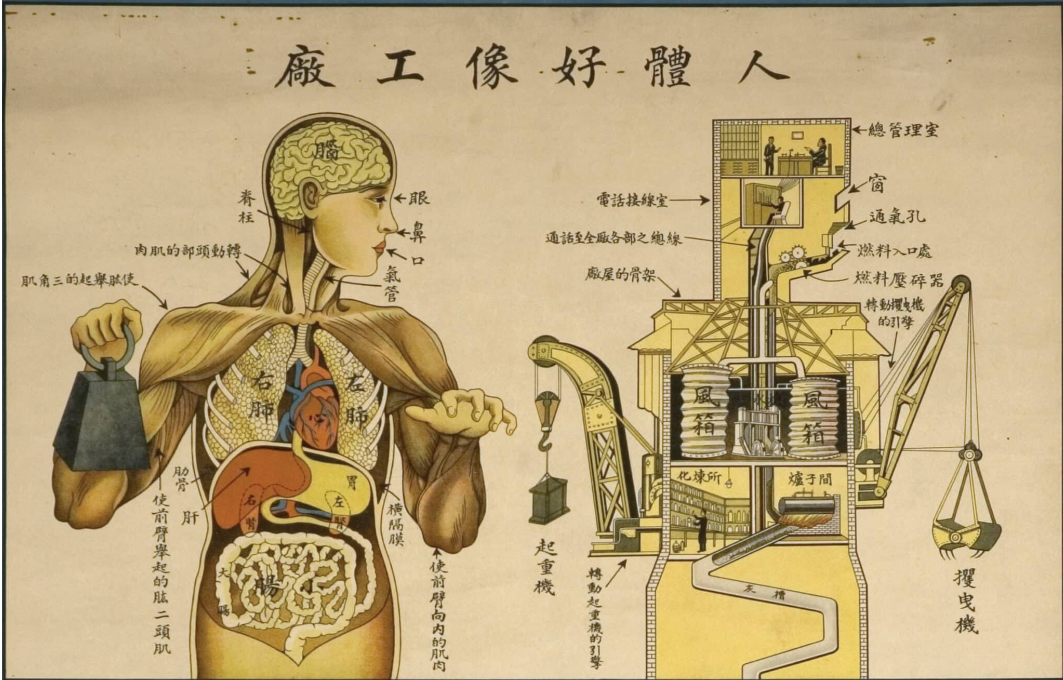

Physiotherapy is dominated by the aforementioned biological essentialist idea of the body as a natural entity reducible to its fundamental pieces, screws, joints, organs - to its [biological] structures and their [biological] functions. Any social factors are secondary to the chemicals, malignancies, displacements. “Psychosocial” questions we might ask are “how does social isolation affect their nervous system?”, or “how does their minority status affect their immune system?” or “do they have family support for their knee rehabilitation?” An infatuation with the biological, under the guise of the sociological or psychological.

No physiotherapist I have met (barring a handful) is competent in sociological theory, so to attempt to competently consider a client’s relevant sociological determinants becomes a dismal failure3.

However necessary it may be to respect all aspects of someone’s health, it is all too tempting to pigeon hole the body into our preferred epistemological categories: a biological body, a lived body (only the person’s subjective experience matters), or a social body. Yet to have a framework which focuses only on the biological arthritic knees and dismiss the vulnerable elderly client in need of comfort is as detrimental as devoting our attention only on their housing conditions, without reference to their genetic predispositions for example. To exclude the disease would be unethical and lead to possibly fatal consequences. To exclude the social circumstance would be shortsighted and exacerbate individuals’ suffering and societal disparities.

Let us for a moment scrap our understanding of the body as the biological body, the social agent or the lived experience but rather we conceptualise the body as one of relations. How might this new perspective open up novel ways of doing therapy?

The-body-without-organs

One pathway out of reductionism may lie in an obscure theory coined by Deleuze and Guattari in their book “Capitalism and Schizophrenia: A Thousand Plateaus”: the-body-without-organs4. Everyone has a body. In fact, we could say all things are bodies: animals, hats, trucks, countries, microbes, etc.

All bodies are in constant relation to one another. Does the mind produce thoughts? Does bone marrow produce blood? One could argue, no one organ actually produces anything; all products are collectively produced by the entire body. Why stop there, when we can argue that the body is produced by a complex of bodies and environments. The body itself produces as much as it is produced by other bodies and it becomes difficult to determine what a body does and what is done to it.

If we accept that a body is both biological (an organism composed of atoms, molecules and cells) and social (an agent that engages with and shapes culture(s)), I am sure we can agree that a body has relations to people and things. The body eats food, sleeps to rest, breathes oxygen, harbours bacteria, reproduces, gets sick, and dies as a consequence of its relation to its world. The same body will simultaneously have relations with people, occupations, groups, the culture it is steeped in, and so on. Human bodies may reflect upon their physicality and place as a social agent and shape an identity as young, old, sick disabled, and so on.

Deleuze and Guatarri called the body that emerges from this confluence of relations the body-without-organs, in contrast to the biological body the-body-with-organs4. For Deleuze and Guattari, the physical biological body (body-with-organs) is not the important body. The body-with-organs is the result of powerful forces emanating from biomedicine and medicalization; clinicians turn bodies into patients and their experiences of disease into case histories5. Deleuze and Guattari are interested in the myriad of physical, psychological, emotional and cultural relations formed from birth. The gendering of a child, the school they attend, the metaphors about the body they are exposed to, their parents' relationship to pain and injury, the routines of work all create the relations that shape the-body-without-organs. These various relations to other bodies (bodies referring to anything one can affect or be affected by) determine the-body-without-organs’ limits. These limits are supple. Always shifting, in flux, and determined by the body’s changing relations to other entities.

Every relation has the capacity to be affected by and to affect another entity, simultaneously creating shifts and changes in one another. The force with which they might affect or be affected can be small and weak (my relation to carrot cake, my relation to the profession, or one’s beliefs about pain) others might be enormous (my relation to the earth’s gravitational field, or one’s relation to their religion).

Deleuze goes on to describe the body-without-organs as a territory. He encourages us not to allow a territory to become static for too long, not to settle down, wall it off and dig a moat. Rather, the territorialized body-without-organs should be deterritorialized and subsequently reterritorialized. It should be sculpted by its ability to be affected by and affect other bodies. At this point we can see why categories such as biological, psychological and social become irrelevant when we speak of this flux of relations. Biological relations (eating) have social relations (being vegan, sitting in a cafe), psychological relations (enjoying the meal, experiencing comfort and nostalgia), moral relations (not eating meat, food being halal), and so on. We begin to think of a body as a multiplicity. A multiplicity because of its multiple relations within itself and between, and among other bodies. A multiplicity of affects.

Instead of focusing on the-body-with-organs, we focus on its relations. As clinicians, we may go from asking the familiar epistemological questions of “what is the body? What is the structure and function of bones, muscles, joints, and how do we fix them?” to instead asking, “what does the body do?” What are its political, philosophical, cultural, biological, physical, psychological relations? How have those relations been affected? How might we create new relations, introduce old relations, or strengthen current ones?

As Deleuze and Guattari suggest, we might even move to asking “what else can a body do?”. To assess what a body can do could once again become about function. A body cannot just become sick or healthy, but can work, can play, can interact. Crucially, the question “what else can a body do?” or “what is the body capable of doing?” or “what are the limits of what a body can do?” expand our imaginations; these questions open up the clinicians/patients’/caregivers’/families’/e understandings of what else this body might do, or how else it may relate to the world.

Strikingly, this requires us to create a new conception of health:

Health is never a final outcome in this Deleuzian perspective. Rather, it is a process, a becoming-other that fluctuates along with the body’s capacities; these capacities mark the limits of what (else) a body can do, but are always in flux, always becoming other. Rather than saying a body is healthy, we might talk about its ‘becoming-healthy’, or about the ‘healthing’ of a body, to remind us of the active processes involved and the fluctuating nature of embodied health. — Fox 20126

Deleuze and Guatarri’s model of the body-without-organs emphasises a body that is active, experimenting and engaged, always with the capacity to form new relations and desire to do so. The more relations a body has the more it is capable of doing; perhaps, the healthier it is.

As therapists we ourselves should not be territorialized but always becoming deterritorialized and reterritorialized. No longer identified by our tribe but by our movement across the landscape. We are becoming nomads, wandering ceaselessly in and out of new territories.

Clinical Perspective

When we examine someone experiencing chronic pain they are met with physical, social, financial, psychological, and behavioural limitations. E.g. inability to flex their spine, isolation and loneliness, loss of work, fear of pain and avoidance of meaningful activities. These limitations are a consequence of the relations they have acquired over time.

Having recognized the questions beyond “what is a body” or “what should this body do,” to the limitations of what a body can do, there is an opportunity to assist sufferers in breaking free from their limiting relations, be these physical, social, behaviour, and so on. More interestingly to me, we ourselves can break free from our own limited identities as therapists. Deleuze and Guatarri have suggested that through our innate creative potential, by changing our relations, we might become something more than our present limited condition.

As clinicians part of a regulated profession and when faced with a client who is vulnerable and dependent on health professionals trained in biomedicine, it is remarkably difficult to resist and ask “what else can a body do?” The trouble with the body-with-organs is that it has become a powerful dominant perspective to the point where it becomes difficult to imagine alternative treatments or rehabilitation programs. What would happen if we resisted a dominant territory, and found, what Deleuze and Guattari called a “line of flight” or “line of escape”. It is an infinitesimal possibility of escape; the elusive moment when change happens.

This can happen by introducing a new force or by strengthening an already present weak force. Any line of flight which causes disruption (deterritorialization) will inevitably lead to an emergence of a new state (reterritorialization), but it may be one where a body can do more (or different) things. Crucially this does not lead to us or our patient’s being restored to their former selves, but rather welcoming and creating a different self.

We can imagine that the body-without-organs is territorialized in client-clinician interactions, bringing with it particular limitations. For example, the clinician meets the client in a clinic room; the clinician interviews the client; the clinician is perceived to hold the knowledge and the client is the recipient of it; the clinician assesses the client; the clinician prescribes exercises; the client expects a physical intervention, and so on. However, all forces can be resisted.

Our client may resist the territorializing force by refusing the sick role or patient role and opt for “consumer” or even “peer” instead. For example, they might bring us a research article and theory about their condition and ask for our opinion. Or they might choose not to take their medication and opt for an alternative mode of coping.

We too can resist physiotherapy. We can resist the clinic, meeting our client in a park instead. We can resist the power imbalance of being the arbitrator of knowledge who provides answers and opt rather for a more equal posture of inquisitive and curious facilitator. We can resist the overwhelming pressure to provide the client with a prescriptive premeditated intervention and rather choose to use our clinic as a space to experiment with the unfamiliar. Some experiments fail, but movement means the opportunity for more movement.

By resisting the dominant, by resisting the approach to a problem which we all recognize, we risk the unfamiliar. Bring something new into the world! Make the familiar strange.

As therapists of rehabilitation, we might begin with: what else can physiotherapy do?

References

-

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F., 1994. What is philosophy?. New York: Columbia University Press. ↩︎

-

Nicholls, D. and Gibson, B., 2010. The body and physiotherapy. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 26(8), pp.497-509. ↩︎

-

Nicholls, D., 2019. End of Physiotherapy. Routledge. ↩︎

-

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F., 1987. A thousand plateaus. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ↩︎

-

Fox, N., 2012. The body. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. ↩︎

-

Fox, N., 2012. Creativity and health: An anti-humanist reflection. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 17(5), pp.495-511. ↩︎